My ‘Remember Me’ quilt is currently on loan to The Quilt Collection, hanging at the huge event, Festival of Quilts in Birmingham, UK as part of The Quilt Collection’s ‘Pattern & Print 1780-1840’ exhibition in the summer of 2024.

This post expands on the significance of the embroidered quotes included in its frames.

I wrote about the making of this quilt as I stitched it back in 2022, and you can read that full post here. In my post about the design and making of this quilt I talked about the inspiration that I took from the quilt makers of the 1780-1840s who sewed beautifully delicate frame-style quilts. The Quilt Collection are showing this quilt alongside their precious historical collection from this period to encourage new work inspired by their collection. You can find these contemporary responses on the outer wall of the exhibition stand.

I touched on the motivation for making this quilt in my original post, describing its role as part of my Masters degree in History at Oxford Brookes, saying..

Yet as I wrote about women who sewed, the absurdity of only recording their life stories in words became apparent. You see, many of the women who asked to be remembered through their stitched work were using this medium (stitch) as their only means of memorial. To then take these carefully expressed stitched messages and only record them in written words was to further denigrate the importance of textiles as an equivalent medium for self expression and autobiography? I knew that I had to also make a quilt which captured and communicated some of these themes. If text and textile were equal modes of communication – I believe that they were- then I had to honour that by producing two ‘dissertations’ – one in words, and one in cloth.

I eventually produced a written dissertation, but I also made a quilt, how could I not? You can read my full written Masters here too.

I’ve since used this quilt to help historians (who often know little about quilts) and quilt makers (who love to see quilts but might not want to plough through an academic thesis) to both share in knowledge about the power of a quilt to keep stories safe. My quilt included many of the hand embroidered quotes that were taken from my research.

At the end of my website post in 2022 I promised to revisit the stories of these women in more detail here for all to read. Well, ha! Little did I realise that I would be plunging headlong into another 4 year academic adventure as I have been working very hard on my PhD thesis, a way to take this work further, sharing it with new and often unexpected audiences, most recently as part of the London College of Fashion where I now work and study.

Taking advantage of my quilt being out on display again this summer it seemed that now was a good time to revisit my original promise. I’m delighted to see my quilt alongside such a splendid array of modern and historical quilts.

I’ll now share a little more about the ways that textiles can function as a text, and what they can tell us about what these women valued and cherished. My intention is that you could read this post before or after looking at the quilt in context and perhaps enjoy it on several levels as you both see and think about what old quilts can ofer us as contemporary makers and historians.

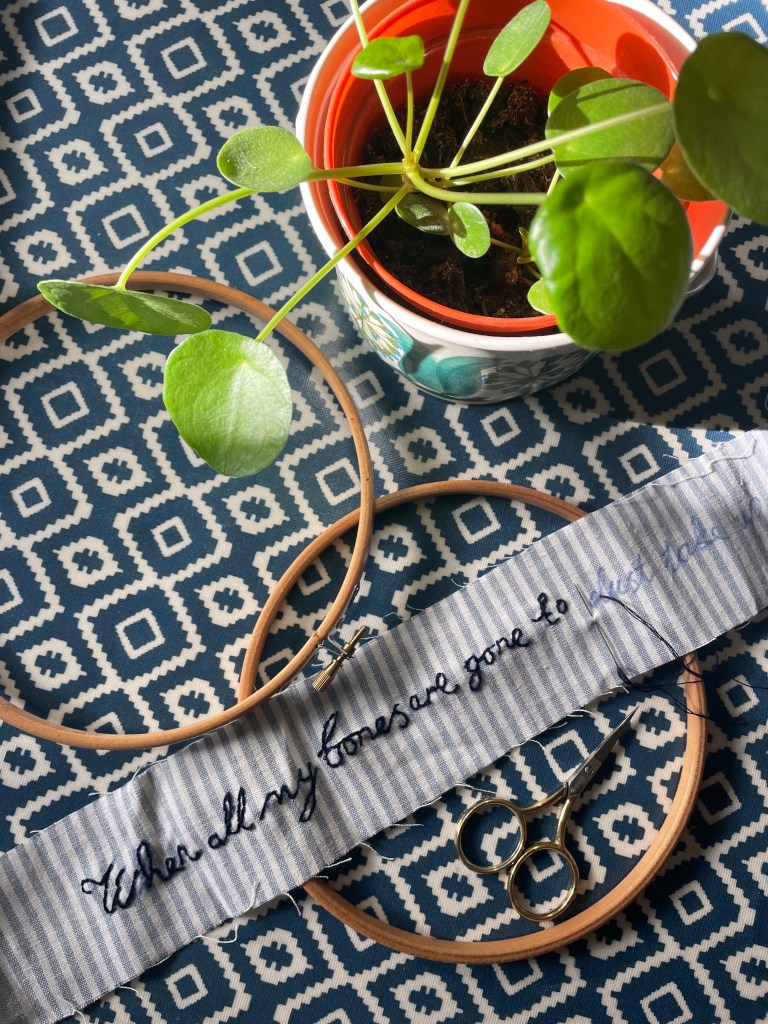

I’ve taken the stitched words I included in a rough chronological order below. I hope that you enjoy hearing the words of makers whilst we consider how quilts were understood as ways to save stories, memories and associations as part of oral and familial history telling.

This Handy Work my Friends May Have When I am Dead (1780)

I chose this phrase as a representative of a whole swathe of emotional and moral messages that young girls included in their stitched samplers throughout the late seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Sometimes they included this embroidered work as the centres of framed quilts. I chose this phrase because it reminds us that women’s knowledge and power was haptic, it lay in the knowledge of their hands which they passed on from one maker to another. In calling her work ‘handy’ this maker was reminding us that the role of much needlework was instructive and as an aid memoire. Without written instruction or many pattern books, most ordinary middling girls relied on looking back at learnt stitches and previous work, or the work of others to remember. In speaking directly to her friends, she reminds us that women’s friendship networks have so much potent historical meaning that remain under historicised in a history still dominated by men and their power and institutions.

Lastly this maker reminds us all that stitched words endure, she addresses her own demise as part of a culture where the recognition of mortality was encouraged as a tool to shape living behaviour, but in doing so she also subverts that statement, asserting that her words will live on beyond her grave. That we keep them alive in new work, in a very different social and historical context reasserts that not all knowledge needs to be written down, that indigenous, social and community knowledge has power and importance, and that we all contribute to that knowledge economy when we sew with others. Knowledge is not just a commodity to be sold in books. Shared knowledge in oral traditions is community power. Our 1780s maker knew this, and we might remember that as we look at her words again today.

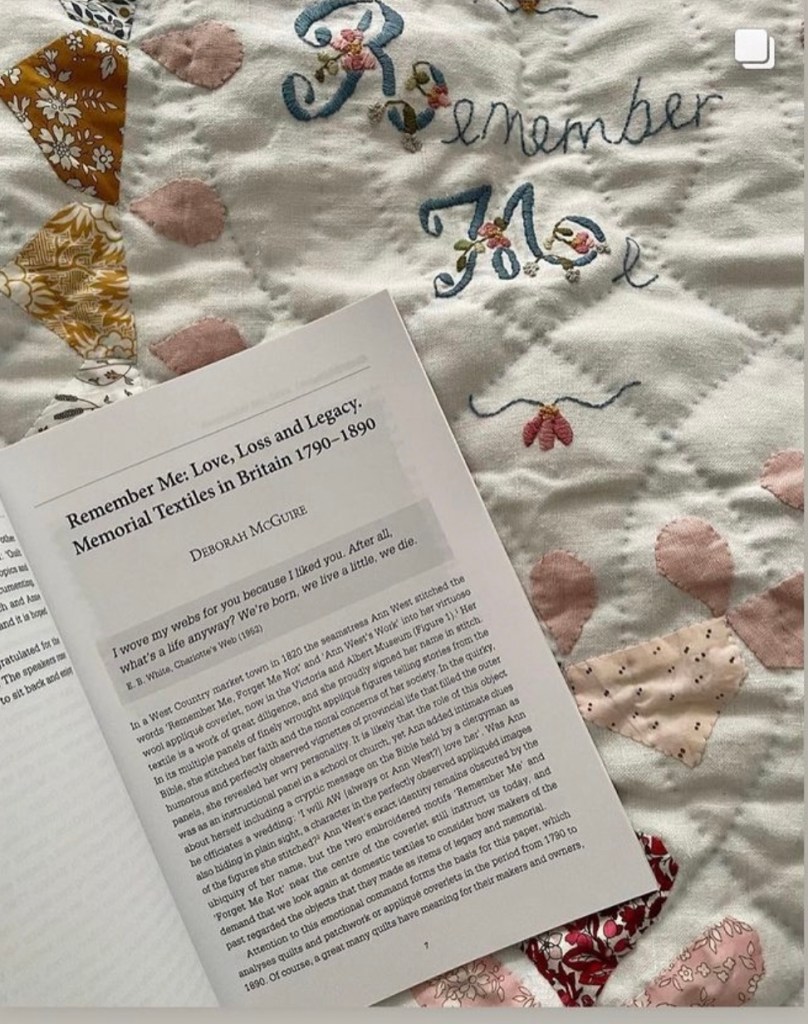

Remember Me, Forget Me Not (1820)

These words echo the phrase stitched in 1820 by the maker Ann West who stitched a complex coverlet, now in the V&A. I’ve talked elsewhere about the power of the words of makers like Ann West who speak to us through space and time with the arresting words ‘Remember Me’. Both a request and a challenge, this small phrase has such power and I used it in the title of my MA study, both to ask that we remember these makers, but also more broadly that we further consider quilt making in Britain within a broader social context. I repeat them as the centre of my quilt as both a challenge and request to viewers of this piece at Festival of Quilts. I research and talk about the history of women like Ann, what their textiles tell us about the past, but perhaps more importantly, I explore their place in social networks and ask what we can learn from them about how we see our own world.

Ann West chose to people her coverlet with the diversity of rural life which included the poor, the infirm, and even the ridiculous as she stitched the characters of her small town. As we look at her work today we might perhaps reflect on her directness as she recorded social inequality, the disadvantaged and the disabled, the persecuted travellers and the tragically destitute. Ann West asked to be remembered, but she challenged us to remember the society and community that she lived within and the problems and challenges that it faced, as much as her own individuality within it. Whilst time changes the details of social problems, the challenges remain very pertinent to us as we look at her cover. When you look at this quilt, do think about what your own work will reveal to future historians about the social web that we all exist within, and how you might place your own values and community at the heart of what you make. For when we look and carefully see what we are asked to remember in Ann’s tiny stitches, we learn about her past and our future.

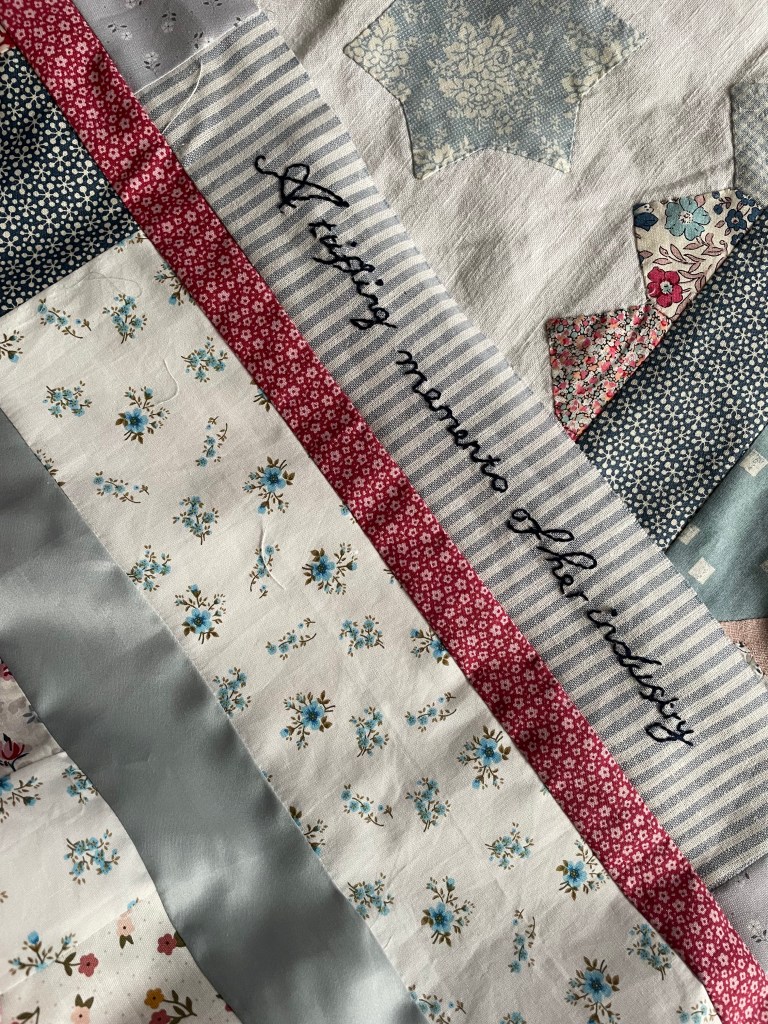

We Love Our Grandmother’s Memory and Delight in Preserving Her Patchwork (1821)

These words came from a newspaper article written in 1821 which was authored by a woman who was the custodian of her grandmothers quilt. She describes the quilt in its old fashioned georgian style for the bright young things of 1821. I chose this phrase because it reminds us that generational change was always a kind of longshore drift in our emotional lives, pulling some ideas and objects into the present and washing some ideas and items away to be consigned to the vastness of history. We can tend to think that the casual dismissal of the work of older generations by younger is something that came after the invention of the teenager, but documentary sources show how enduring these reactions have been, and patchwork and quilting are often used as the prism through which generational conflict can be played out.

In the early 1700s a correspondent complains about her giddy nieces who would drink tea ( a new fashion) rather that work at their frames. in 1821 another 100 years later the same dynamic is played out by this granddaughter who declares that the quilt is saved because of the love of their grandmother rather than its aesthetic qualities. I am often asked when I talk at quilt groups whether quilts made today will be kept, and this causes great anxiety amongst many makers. Often grandchildren honour what children dismiss as old fashioned, and this leapfrogging of fashionability and declasse views between generations, or sideways through godchildren, nieces and nephews or friends and neighbours is a process of interest to historians.

Above all this phrase encourages us to to think of our production as cultural work, creating objects which we cast into the sea of generational material culture to maybe wash up as a cherished piece which can transmit or evoke emotions in the future, or perhaps be destined to do that work in the present, used up and only visible in an account like this makers. Either way, when we create something unique and individual, we make a mark on history, the key is in how we read these marks. Recognising that generational ambivalence was always a threat to the heirloom perhaps gives us permission to relax a little and consider our own work as ripples in the sea of history that make make big waves or just be recorded in a small but powerful line like this.

My Whole Life is Traced out in your Bright Squares (1838)

The timeframes that quilts work within can be a single lifetime or multiple generations. This quote is taken from the account of a woman who had spent time living overseas, and then returned to Britain ‘expecting soon to be at peace’ and in doing so was reunited with a patchwork quilt that she had used in her youth. She uses the patchwork to explain how she associated memories with patches which anchored her to a sense of home and to memories of her childhood ‘its varied and once gay colours, like myself now faded and dull’. The emotional work of this patchwork is done in one lifetime, reminding a maker of their own history, perhaps in ways that could then be recounted to others. By writing down her feelings about the quilt she extends its emotional impact beyond her own life span. Most makers do not record the meaning of their made objects in print in this way. Most commonly makers rely on the power and longevity of the spoken word.

The value of oral histories is intertwined with objects like patchwork quilts because of the evocative value of old textiles to provoke memories. In a time before photography, and in a period where the speed of change made many anxious to retain a sense of their pasts, they used objects as the way to associate memory and summon up its recall. Despite the memory prompts of images, we often still feel that the squares of patchwork can ‘trace out’ our whole lives. Remembering the ways that life has changed us, but also recognising threads that link us to our past can come from the examination of old quilts. In making new ones we honour these shared experiences of fragility and mortality that are reflected back to us in quilts and accounts like this.

I Have Made Patchwork Beyond Calculation (1843)

This line came from the account of her lifetimes work by a woman called Catherine Hutton (1756-1846) who left us some of her extant work along with a published record, written in 1843 when she was almost 90 years old, which list her labour. Catherine challenges the modern understanding of her very gendered work life as ‘leisure’, whilst making us aware of the confines that late Georgian feminine expectations of a domestic life set on her ambition. Catherine was independently wealthy enough to not marry, but could travel widely and to have a rich social and academic life as she corresponded with authors and scholars of her time.

In her final reckoning of her life production, alongside the garments she stitched for herself and others, the places that she visited, the care for relatives and friends, and the literature she read and wrote, she listed her stitching virtuosity, declaring ‘I have quilted counterpanes and chest covers in fine white linen in various patterns of my own invention’ and ‘I have made patchwork beyond calculation from seven years old to eighty-five’. I chose this line for its expansiveness, taking up space historically denied to women, but also owning the oft stated triviality of patchwork by hostile commentators and reframing it as an epic and life long undertaking. For those, then as now, who saw patchwork and quilting as meaningless distractions ‘cutting up perfectly good fabric into pieces and sewing it back together again’ – she presents this work instead as if we were to say to a stonemason building a cathedral that their work was just ‘chopping up perfectly good rock and putting it back together again’. She states through her choice of phrase that she is both an artist who invented her own designs, but also a craftsperson whose devotion to the perfection of a skill was earned as it spanned a lifetime. When Catherine began stitching in the late 1700s her work was considered genteel and moral, by the middle decades of the nineteenth century when she wrote this its value had travelled down the social scale and was being subjected to the intense misogyny that often accompanied Victorian views of women’s ‘handicrafts’.

Catherine reminds us that societies stated or published wider view was very often not one shared by women makers themselves. History is written by powerful observers and the women who made textiles seldom wrote about it. In her rich accounts we see how she understood her work as valuable, as having wider meaning to her friends and family, and how she saw it as a reflection on her own values and priorities, listing how she spent her days and years and decades and life and accounting for that time with the same satisfaction that any workman was afforded as he surveyed the buildings he built or furniture he crafted. Catherines statement reminds us that we can actively participate in how we create and shape the context of our own work. We can belittle and trivialise it or we can own it for the meaningful, socially connective and emotionally sustaining labour that it is. The difference is that we have so much more choice, even if those choices are still imperfect, choice which was often denied women like Catherine Hutton.

No One Can Look Upon the Needle Without Emotion; it is the Constant Companion Throughout the Pilgrimage of Life (1844)

This line appears in a needlework instruction manual from 1844 which I chose for its ability to highlight the sense that the needle is more than a trivial tool, it is in fact a form of emotional expression which can be formative in the sense of self and wellbeing in both nurturing and nefarious ways. This statement suggests the widely understood role of the needle as an emotional tool, yet it is hidden in a book full of instructive do’s and don’ts which came to rule needlework expression as the century went on, and which still cast a shadow today.

In 1844 the needle was universally understood as women’s lifelong work. In recent generations the needlework of women from that period has tended to be analysed through the lens of how this expectation constrained women, and that critique is just. But today a more nuanced discourse is emerging, perhaps informed by new generations of women scholars today who were not taught needlework as part of education, and thus have had freedom to choose it in life. The freedom from didactic oversight perhaps allows us to look back and see the ways in which individual women, despite their wider oppression, personally often embraced needlework and found power, comfort and solace in its rhythms.

Teaching quilting to the public in the 2010s I often came across people who still expressed ambivalence in stitching, scarred by over-prescriptive teachers of their 1950s and 60s youth. As a child of the 1980s and 90s schooling system the needle had already been sidelined as a tool of gendered obsolescence, and thus I came to sewing without coercion and instead found a haptic practice which only expanded my life instead of shrinking it. My privilege is to be born today instead of 1844 where my choices would have been much more rigorously constrained.

The words the writer used in describing the needle as a ‘constant companion’, in this statement could of course be read oppressively, but then as now they perfectly evoke the place that needlework had in many makers lives. They describe the way that needlework sits so close to the body, always an arms length away, in the lap or tucked alongside in a chair, to picked up in moments of quiet or distraction. The bodily intimacy of needlework practice is often overlooked. It’s an aspect that is often remarked upon in other artistic mediums, but needlework is particularly evocative with its tactility. Whether from need or choice the needle was there through thick and thin, and it offered solace and comfort for some and a welcome but imperfect way to support themselves for others. This statement from the past reminds us that the needle can be a friend as well as a dictator and that could be true in the past as it still might for some today.

A Trifling Memento of her Industry (1861)

in 1861 Mrs Ayscough of Humberston/e in Lincolnshire died in her hundredth year. The event was rare enough to make the newspaper in 1861 and her family wrote an elaborate tribute to the much loved family member. They described her devotion to family through the means of an epic labour undertaken in the last two years of her life. Describing how she had undertaken to make ‘well-made bed quilts’ for each of her daughters before she died, they proudly related that she had succeeded in this task. These kinds of eulogies, epitaphs and obituaries are not uncommon in the late Victorian period, indeed through time women (when they are formally recognised at all) have been memorialised through their domestic and familial work.

Yet behind the formulaic notion of these words lies an emotional truth; that family members do remember each other through the relationships that they enjoyed, and objects like quilts are a tangible way of measuring, or even memorialising the extent of that devotion. By evoking the ‘well made’ phrasing, or in other examples listing the number of pieces of patchwork or the time spent working on the quilting, these families find a way of measuring the unmeasurable; the extent of a loss or the esteem that a person was held in.

This family also use a phrase which I first found confusing, perhaps dismissive, when they described this feat of making as ‘a trifling memento of her industry’. But, of course, by juxtaposing the momentous feat of making numerous ‘well made’ quilts in her 98th and 99th year, EVEN this was nothing to the extent of her labours for family and home over the other 98 years. The writers relied on the fact that readers would immediately understand the extent of this work, in a time when quilt making remained more commonplace amongst middling and working rural families in the provincial hinterlands, and they trusted that this would accurately convey what this family member meant to them.

In a time when, despite advances in women’s participation in the workplace, many women are still questioning the often burdensome balance of paid and unpaid work that they undertake, this kind of obituary remains as complex to process as ever. Whilst the opportunities of paid work were denied many women in the past, the unpaid work of a lifetime of family care remains a reality to many, whatever family situation or shared care partnership we may now chose to live within. How we choose to remember how we spent our time in life is a timeless concern. Whilst public professional successes are now available to women as well as men to be included in an obituary, it remains the case that for both men and women, quantifying the extent of the emotional bonds that characterised their life remain one of the most important aspects of how they might be remembered. Mrs Ayscough invites us all to think harder about how we interpret the words that surround needlework in the past, and encourages to think about how we might wish to be remembered too.

To Be Kept in Remembrance of Her as an Heirloom for the Family’ (1878)

Lauderdale Ramsay (1806-1888) was born the daughter of a baronet and married a baronet and lived in a castle surrounded by 300 years of dynastic portraiture and fine furnishings, but she chose a coverlet of her own making in 1878 as an unlikely place for a personal memorialisation, words from which I include in my quilt. Her emphatic self memorialisation reminds the owner of the quilt of her status, and demands that she be remembered through her needlework, stating that the coverlet be ‘kept in remembrance of her as an heirloom for the family’. In doing so she elevates the product of her making alongside the grand portraits and priceless furniture of other makers, craftspersons and artists as a worthy and appropriate piece of material culture to be preserved as a form of familial and wider cultural capital. She speaks of her self in the third person, and includes both her birth and married peerage titles to underline the important lineage and pedigree of her work, but she does this in a medium that, at that time, was largely dismissed as parochial and bourgeoise. I wanted to include this statement because it really challenges everything that we have been taught to believe about what forms the cultural heritage of our nations society.

Whilst the stories that we are exposed to associated with history are often situated in stately homes like Lady Burnetts, their contents are increasingly challenged and contextualised as we confront British colonialism. But within this new lens there is also a justifiable reckoning that remains unfinished about how we tell the stories of the women, both rich and poor, who lived within those walls. Family history has been for too long patriarchal-family-history. Those of you who use genealogy sites will attest to the difficulties of tracing matriarchal histories which leave us not with trees which reach up and back in time, but more often wide, sprawling matriarchal structures which map and overlay these patriarchal trees with the bonds of women, their mothers, sisters, cousins, nieces and female friends. To use the natural history analogy, instead of a forest of tall and seemingly unconnected trees ( male patriarchal family names), we instead reveal the wood-wide-web ( female matriarchal and sororal bonds) a rich mass of roots and branches, the shrubs and foliage, the mushrooms and fungi, the crucial web of ecosystems which keep trees alive. In using a feminine, domestic and intimate textile as her memorial, Lauderdale, Lady Burnett, with a nod to the patriarchal families she is defined by instead uses a tool of feminine networks of emotional connections – the handmade quilt.

Quilts are a crucial portal into this unseen web, mapping where connections matter and how women used other means than inherited property and fine art to assert their centrality in family history. Instead they created their own heirlooms and labelled them as such in stitch and in oral histories as they passed quilts and other made items through generations. Just as in a wood we can now bring to life otherwise unseen connections through the new knowledge that they exist, in women’s history we can use objects like quilts to reanimate the bonds that were always there, but were seldom recorded.

I included Lauderdale Ramsays words to remind us of that. As an elite woman she used the methods of her class – inscription – to make her legacy visible. But many other less aristocratic women did the same, instead relying on oral histories passed from mothers to daughters and sons, and nieces and nephews to tell when an object had importance. We receive these items into museums today, often still with some scepticism as to the validity of told stories, instead asking for history in tangible print – photographs, family tress, letters and documents. We will know that the work of gender equality is done when oral histories hold the same weight, and are seen as equally as weighty sources, and objects like quilts are the way to access these stories.

I hope that you have enjoyed taking a little deep dive into the thinking and research that sit behind the making of this quilt and the writing of my thesis. You can, of course, enjoy reading the full thesis via my website or on this link , with references and further reading on all of these examples and many more, and you can see the quilt that I made from Weds 31st July – Sunday 4th August 2024 at The Quilt Collection Exhibition Pattern and Print at the Birmingham NEC. Tickets are available here.

Amazing article! Synthesise so much of what I love and feel about sewing generally (I make historical costumes too) and quilting in particular. So much shared enterprise, social history, company kept, family documented – whether subversively or reverently. Will be reading your thesis too. very good luck with the PhD!

LikeLike

Great article Deb. I’ll need to read it again after seeing the quilt. Sorry not to see you there.

LikeLike