My academic work explores the role that quilts played in the lives of the people who made and used them in the past. But, as we all recognise, the past is a different country. We can only speculate as to how emotions were actually experienced by individuals in the past – their world, experiences and contexts are not ours. It is not just feelings which are hard to translate across centuries. The fabrics that were available to quilt makers of the past were also very different to those we most commonly use today. Alongside this many of the practices of quilt making have changed beyond recognition. Yet old quilts have survived, and in their materiality lie hidden secrets about the labour that made them. It is this labour that fascinates me, and which I set out to recreate to answer some of the questions that these beautiful textiles ask of historians today.

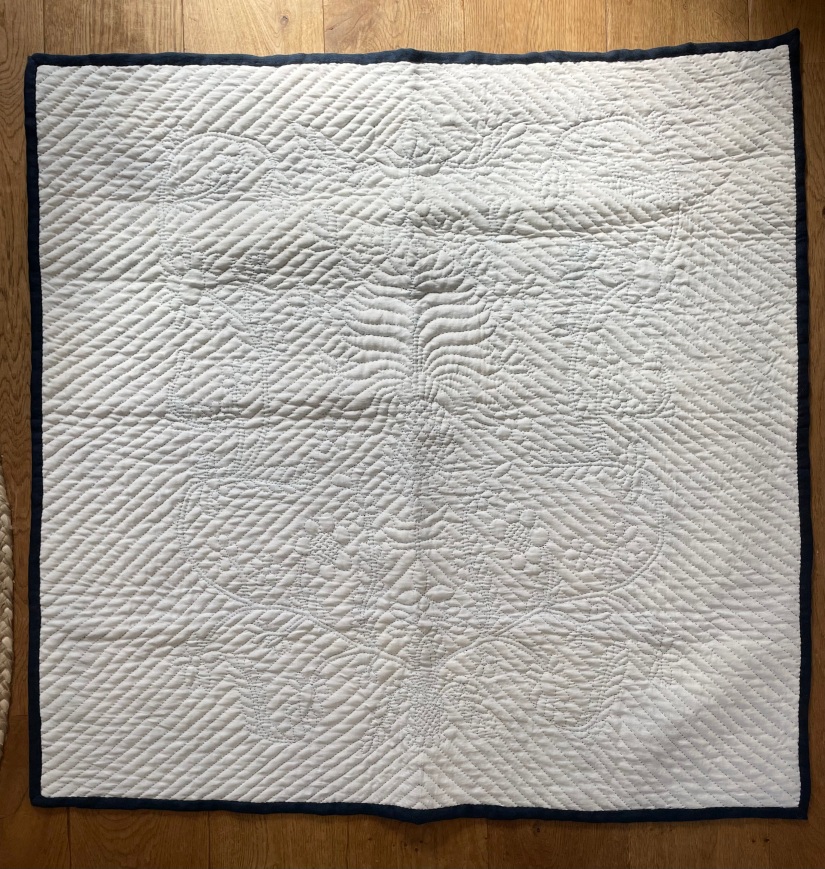

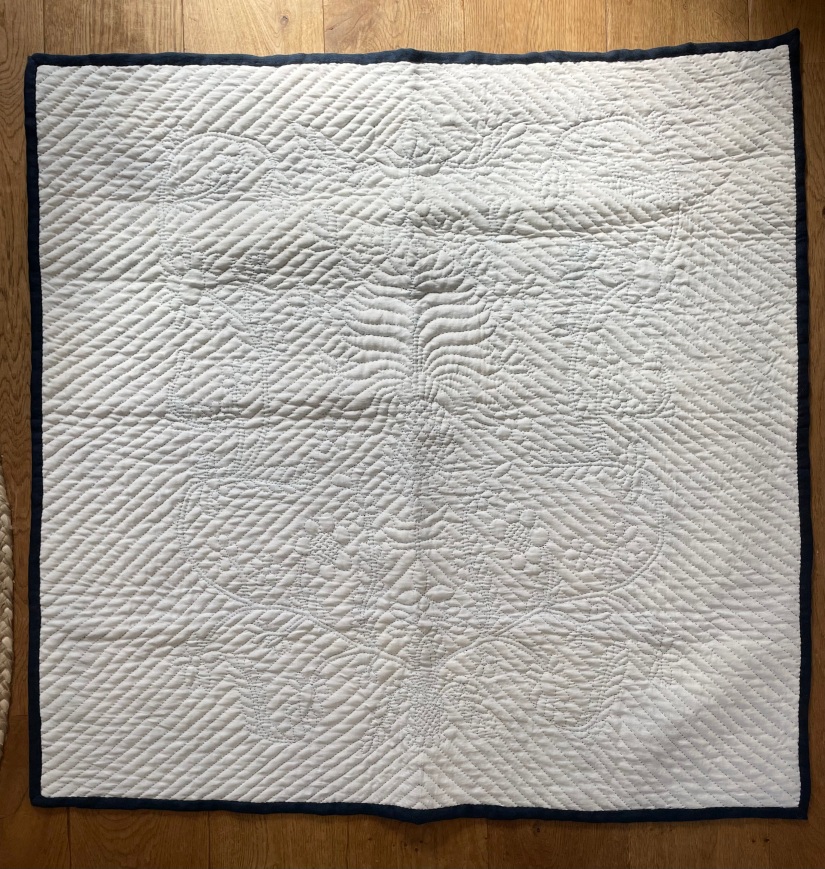

As part of my work I have enjoyed revisiting the techniques and methods of quilt making in the past to explore how quilts were made and experienced by their owners. From eighteenth century silk petticoats to 1920s north country wholecloths I have sought to experience the labour of making through the eyes of the past. Woollen wholecloth quilts like the one pictured above, were clearly always hand quilter goals – both then and now. The dense quilting, elegant floral designs and wool construction are seldom seen amongst quilts being made today, and thus their construction asks lots of questions, which we don’t have all the answers to. I wanted to explore making a modern version of a wool calamanco quilt to investigate some of the questions that plagued me when I looked upon this beautiful textile.

Of course, women’s lives were always poorly documented, and the further back into the past we travel, the less women wrote ( or the less likely it was that history kept their records) about their practices or feelings. Yet quilts are particularly fluent sources to suggest to us both the practical technicalities, as well as to demonstrate how feelings were enacted because so many quilts have been preserved. Their preservation has largely happened outside of institutions until the 20th century, held within chains of matrilineal or patrilineal family or passed between women friends. In these acts of emotional preservation, are traces of the feelings about the value and worth of a quilt and the importance of its preservation – secured by these actions. The extant quilt which inspired my make (above) was such a quilt. It dates from the last decades of the eighteenth century and it survived within generations of a family called Copp in New England, USA for two centuries before being passed to the Smithsonian Museum in Washington D.C in the 1960s.

I have always been borderline obsessed with this quilt’s virtuoso quilting and its unusual-today wool construction. When the American Quilt Study Group set Indigo Blue as their prompt for quilt study in 2023 I knew that I wanted to explore this quilt. Yet it is also important to also recognise the long history of indigo, not least its troubled role in colonial North America, a skill and trade entangled in the wicked trades of human life and attached to the flows of cotton.

All aspects of women’s lives are under recorded, particularly the kinds of skills which were carried in oral traditions; the skills which women taught each other by showing and doing. It was this way that the skills of indigo dyeing likely came to the US. Anyone who has tried to write an instruction for a physical act like reading an indigo vat or forming a stitch, will also recognise that writing was a second-class way to pass on knowledge. It was, and still is, much easier to demonstrate skills such as loading a quilting frame or executing hand quilting by showing, than by writing laboriously each nuanced movement of a body. If the written records of the past are scarce (quilting, most often carried out by domestic women is particularly sparse in instructional records, Indigo dye practices were most often carried by non-white women in this era) we still have access to bodies. Whilst bodies are also undoubtedly changed since those inhabited by those who made indigo dyestuffs or sewed this quilt, nevertheless bodies also exist as tool for historians to explore, as we seek to recover knowledge of quilt making in the past. One of the methods we can turn to, often used by dress historians but also useful in order to understand how quilts were made, is carrying out a re-creation.

The AQSG bi-annual Quilt Study is an example of how historical research and modern making can work side by side. I always emphasise that an important purpose of my historical research is to inform new work. Whilst I love old quilts, I also delight in new quilts which reference their complex past. For this Quilt Study I approached The Smithsonian who gave permission for me to create my own pattern from the digital image of this quilt to be remade into my new textile. You’ll likely recognise that this style of quilting design is closely related to the kinds of quilted designs being rendered on silk and wool petticoats in this era too. We also see these designs in related needlework such as crewel and bed rugs and fine white on white embroidery of this era. Yet to a modern eye, pairing a quilt design so detailed with a fabric like wool, was clearly a challenge to create definition. I was intrigued to play with the texture I could create.

The original quilt was one of three late-eighteenth-and-early nineteenth-century quilts that were donated by John Brenton Copp of Stonington, Connecticut to The National Museum of America. All are a part of an extensive gift of household textiles, costume items, furniture and other objects that belonged to his family from 1750 to 1850. The Copp family, originally from London who sailed for America in 1635 aboard the ship ‘Blessings’, were later in the dry goods business, importing and selling textiles, which probably explains why their household had such a wealth of textiles, and perhaps why they were preserved. This collection of textiles offers insights into New England family life of that period and you can read more about it in Copp Family Textiles by Grace Rogers Cooper (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1971).

The Copp quilt is made of glazed wool. The fabric was dyed blue with indigo, one of the oldest dyes used for textiles and appreciated for its colourfastness and rich deep colour. Glazing, a process involving the use of a hot press on wool fabric, resulted in a smooth, lustrous surface. The lining, a butternut-colored wool, was likely made from two different blankets, perhaps homespun. It is quilted with a popular motif of the period, a large pineapple, using blue wool thread, 7 stitches per inch. A quilted flowering vine extends from a basket at the bottom edge of the quilt and frames the pineapple. A family member, John Brown Copp (b. 1779), was known to have drawn designs for white counterpanes for the young ladies in the Stonington area. The quilting pattern on this indigo wool quilt is similar to the embroidery pattern of a white counterpane, from about 1800, which also belonged to the Copp family. Women’s diaries from this period in New England reference fabrics being woven for quilt making and threads being spun to use for quilting, so we know that these quilts were part of the seasonal making calendar of generations of women in this period.

The first challenge I faced was how to find a modern fabric appropriate for this project. American scholars such as Lynne Zacek Bassett have researched textiles from this place and era extensively – do check out their resources to learn more – but it was clear that the kinds of woollen fabrics available today were radically different to those available around 1800. A navy wool fabric didn’t seem impossible to source today, and navy was one of the most popular choices in this historical era due to its stable dye, but calamanco was a thin fabric of worsted wool yarn which could come in a number of weaves and was usually glazed or pressed or calendared for a sheen so characteristic of these quilts. Today, when we think of wool we tend to think about fabrics that are thicker, but in a time where cotton was still scarce and wool was ubiquitous, fine woven wools were widely available for clothing, furnishing and thus quilt making. Glazing and calendaring wool were processes which treated wool fabrics using hot metal rollers to give them a sheen and make them dirt resistant, again a process seldom seen today in the usual fabrics that quilters might encounter. These fabrics were also particularly associated with textile production in Norwich, England, so perhaps the fine indigo wool travelled to America for export, or perhaps it, or more likely the backing, was made locally in New England.

After lots of fruitless research to match these historical fabrics with modern alternatives for my quilt, I settled on a beautiful linsey-woolsey fabric by Merchant and Mills, made of a linen and wool mix – not historically accurate for these quilts (they were more often 100% wool weaves), but it was fabric that gave the required amount of drape at a thickness that could be quilted, in a fabric that was at best period-adjacent, being used extensively in dressmaking at this time.

Next up I needed to figure how I might transfer a pattern this complex onto a fabric with an open weave and uneven surface such as my wool/linen mix. I tried chalk, pounce and pencil but none would either show up or last long enough on the deep indigo to be quilted in the frame. In the end I reverted to using a 100% linen for a backing to help me with my patterning. I would quilt this wholecloth ‘upside down’ – ie lighter plain side up, a common approach in the frame in the past. I couldn’t find an appropriate blue linen, so went with a white linen sheeting off-cut in my stash with the plan to dye the whole textile indigo after quilting*. On the white smooth linen I was able to draw the pattern in pencil, as you can see below.

*I am yet to finally dye this quilt, I’m still pondering how I feel about completing an indigo dye at home, or opting to keep it white to best see the pattern on fabrics without the pattern-highlighting benefit of period wool calendaring?

What did I learn from this stage of the research? Well firstly that the material and haptic range available to us as quilters today is so narrow. It is well explored in research literature that makers in the past had a vastly superior material literacy when it came to fabrics. Shopping for dress and furnishing fabrics in a society where almost everything was made up bespoke meant that women and many men possessed detailed ability to assess fabrics in ways that we have lost. Secondly, it is clear that the range available to us has shrunk radically. Calendared wools still exist, almost exclusively used in male suiting, but fabrics used in quilts today seldom include textiles like this, and the costs of such fine wools is also a barrier ( although they were premium in the past too). Textiles were always global commodities, but they also reflected local conditions. In a country where wool is so undervalued today, I’d love quilters to embrace the tactile possibilities of wool quilts more. History shows us that wool was a wonderful textile to quilt with.

Next up I considered the wadding. When I made my Georgian silk quilted petticoat during the first lockdowns in 2020, I necessarily drew on what I had to hand and used a cotton domette as my wadding, but after looking at many extant quilted petticoats as part of my research for my PhD since then, I could see that the loft of wool waddings, which were the most common wadding in that period, meant that these tightly spaced patterns could really sing.

I decided to use wool tops and comb my own wool to lay as wadding in this project. In my research I have come across several sources which describe in detail the preparation and amount of wool wadding required to complete a quilt top. Like everything else in the practice of quilting in the past, a knowledge of how much wool to include in between the layers of top and back would have been learnt by watching and doing. I had to rely on the rare records which stipulated wool by weight for filling a quilt, washed and unwashed, which then allowed me to pro rata to figure out a rough volume per square area. It wasn’t too scientific, but I figured that the proof would be in the final loft.

Today we hardly consider wadding at all, other than to perpetually struggle with the basting of a quilt. Ironically in the past there was no problem with basting because the wadding was an organic process which evolved with each pass of the quilt through the frame. Like so many aspects of quilt making, our foremothers had already ironed out the perfect way to ensure a regular even layer was to leave the centre available to be adjusted and reworked as we sew. In our modern haste to abandon the frame we have thrown some babies out with the bathwater, it often seems to me. Beyond the practicality of this process of combing and laying wool, I discovered a whole new process of wool treatment which enhanced the pleasure of quilt making. Working with the wool, gently teasing and placing it was a new layer of engagement with the quilt, returning agency and sense of control rather than inducing anxiety.

The different texture of a pure wool wadding was also a voyage of discovery. Modern wadding is most commonly prepared on a plastic scrim, a kind of mesh which the wool is felted onto to allow it to hold together in a sheet which can be rolled on a tube or wrapped as a sheet. In quality wadding this scrim is often very fine, but it changes the way that wool fibres behave. When pure wool is laid on your quilt you have complete control on how dispersed or gathered it is, how layered you make the wadding and how evenly it is distributed.Modern quilters have a kind of fear of ‘shifting’ in the wadding, but this process showed me that wadding was supposed to be moveable. As you sew each line the wool is marshalled into furrows which expand the texture of the piece upwards. It truly is a tactile pleasure to quilt. As you add extra lines to the piece this volume can be corralled, and the wool takes on a denser, more tensile nature. Instead of seeing wadding as something invisible, it becomes a participator in the final quilt, an essential element with its own personality and behaviour. This aspect of quilt making is almost entirely invisible to modern makers. Instead I found myself thinking more as a sculptor, considering the pattern and its needs for highlight and the density of my stitching being the aspects which affected how I laid down the wadding.

The textures which you encounter as you stitch using these natural fibres is very different to the tactile personality of cotton. The billowy softness of the wool, the gentle give and pull of the linen and wool mix, and the texture and drape of the linen act together to make something much more pillowy than the way we think about cotton quilts. The language of quilt making, particularly through the latter part of the 20th century has become very unyielding. An emphasis on accuracy, 90 degree angles, flatness, straight lines are all at odds with the organic body of this quilt. I hope that the picture below illustrates more generously in image form than I could hope to explain in words – if only you could reach into the screen and feel its yielding softness.

Of course, designers of the past understood these parameters of material and design, perhaps that is why their Rococo inspired patterns match sinuosity with open floral blooms, all set off to best tumbling advantage through their juxtaposition with the tight regimented lines of the background. The regimented needs of machine sewn quilting has also caused us to ignore these forms of quilting adornment. Modern machines can only sew without stopping continuous patterns. The hand quilter can travel and change direction, thus a whole period of quilting pattern of this style is also seldom seen today in our modern obsession with clean lines and minimalism. It seems to me that the charm of these complex quilts lies in their juxtaposition of sinuosity and straight-line. There’s much to inspire modern quilt makers here.

These textures are also kind. Kindness is another quality in modern quilt making which can feel lost in our culture of quilt ‘showing’ ‘judging’ and ‘competing’. These historical material textures work with you, easing themselves into fullness, filling up areas which might otherwise not lay flat, shifting their bias to lay flat to accommodate their neighbouring textiles. Accommodation is often depicted as a weakness today, but making others feel comfortable, offering care and covering vulnerable bodies has always been an important part of the role of the quilt (Although, of course, historical quilt makers’ societies had significant issues of non-care to many, before we get too far into this analogy). Suffice to say that these historical materials pushed me to think again about the parameters that we set on quiltmaking today and how they are an anathema to the extant quilts which exist before Victorian cultures of competition made them public objects. Should quilt be perfectly square? I seldom encounter an old quilt which is.

So what did I learn from my foray into life as a Georgian ( or more accurately for this quilts roots, the Federalist Era in the US) quilter? Like all experiments in time travel we cannot accurately recreate the past, but we can use the experience of trying to understand how materials and tools shaped how quilts were made. In doing so we can also reawaken understanding which may have otherwise been lost by the passage of time. We know that history has not been kind to women’s knowledge, by recreating their work we can revisit its challenges and trials – but we can also re-celebrate its pleasures. Modern feminism explores more widely than ever the ways that knowledge rooted in the sensuality of women’s labouring lives in the past has been lost; a modern exploration of sensuous and haptic knowledge can help to address this. To explore what things felt like, what skills hands and fingers needed to ‘read’ material production, the way that skills were lodged in the ability of makers to feel quality and virtuosity, are all ways to bring back some of what it was to feel in this period.

As a modern quilter I had already returned to the frame, my experiments also explore its parameters, reminding us of why this tool was so intimately associated with the way that old quilts look. By expanding my material repertoires into wool, and wool/ linen blends I have a new appreciation of the wide range of textural experiences that quilting with only cotton narrows our eyes to. The sensuous experience of combing and laying wool and its transformation between the stitches of the quilt has awoken a need for a more haptic pleasure in quilt making to be part of my making experience. I now appreciate just as much how my quilting feels as how it looks.

I’d like to end by encouraging new makers to take inspiration from the past, widening more routes into valuing quilt study. You might not want to make a quilt that looks THE SAME as an old quilt, but making a modern quilt which can trace its roots back into the past is a far more beguiling experience, and is also the work of preserving often marginal makers histories.

I hope that you can also bury your hands into the quiltmaking materials you use at home and make a similar audit. Perhaps as quilters, as we societally move beyond an industrialised age where speed and consumption are most valued, we move to a place where the rich and gentle experience of quilt making is more valued. A place where we recognise that time spent in quilt making ought also to feel as good as possible, and that quilts be a representation of this care for ourselves and our planet. If we reengage other senses than just how a quilt looks, to explore how a quilt feels to both make and use what other changes flow from this shift in values? How does this change how we see, use, value and judge quilts and quilt makers?

Whether in 1790 or today, it remains the unalterable fact that a quilt most often is an object of tactile use. Thus, how it feels is at least as important, perhaps more important, than how it looks? As we labour, making a quilt, we ought to be alive to that sense, judging how texture can be an important part of the creative journey of making. As I sit at my frame, gently smoothing over the soft wool backing, or teasing my hand through the wool roving to test bounce or loft and feel for burrs, my hands are as alive to the feelings of making as my mind. As we all search for mindful engagement with the world, listening to what our fingers tell us about sensual pleasure is an engagement that is enriching. Yes we want to make beautiful objects, but we should also value beautiful feeling objects, for there the real enjoyment of being a quilt maker surely lies?

As ever, looking back can yield valuable lessons about how we move forward. The world has a surfeit of fabric of dizzying array. The quilt frame equalises these different fabrics, making the quilting of different weights and tensions of woven fabric easier to manage. A sensual approach to quilting encourages the sinuosity of shape over the rigidity of straight lines, a more welcoming way to think about what we make and how different fabrics impact the final quilt. If we can widen the lens of what tools and fabrics we use to make a quilt and how we judge a quilt there is such a wide potential of new fabrics and textures which awaits us. I hope that this experiment encourages more makers to think about how we can embrace this diversity to welcome back lectures of wool and linen into the making of modern quilts today.