This Christmas my family made a rag rug together. Like many families in this mad and increasingly bad world we are treasuring and prioritising analogue entertainments as a bulwark. Despite the global chaos, 2025 was for me a year dominated by the connections and comforts that the four humble pieces of wood that make up the quilt (or rug) frame can bring about. I wanted to mark this tumultuous complexity at the year-end with a project that bought me back into intimate creative collaboration with the frame, doing what it always does best – convening genial togetherness. This Christmas we decided to experience the frame differently, and make a family rag rug.

It has been an unusual year which led me to this undertaking. At the end of 2025 I was awarded the Patron’s Award for Endangered Craft, a recognition chosen by HM the King Charles III and bestowed by his foundation The King Charles III Charitable Fund on behalf of Heritage Crafts. In the summer of 2025 Within the Frame succeeded in getting Hand Quilting in the Frame listed as an Endangered Craft in Britain, safeguarding its future and drawing attention to its unique place as a working-class, rural, women-led commercial and domestic craft. It was a lot.

It was thrilling of course, but also rather overwhelming. The award reflected my own long creative commitment to hand quilting in the frame and the academic research and advocacy work that Dr Jess Bailey and I led for Within the Frame which led to the craft receiving protected status again. After a long 100 years where the continuation of the skills of the frame lay in the hands of only committed individual women makers who practiced and taught locally, it is now finally back on the radar of those whose role it is to help preserve and reinvigorate these craft skills nationally.

The imperative last year to gain this national status took over our creative and academic lives, we felt a huge weight of responsibility to makers of the past, but also those working today and in the future who might be more likely to engage with the skill now because of these protections. When the Critically Endangered status was awarded in May 2025 I felt an overpowering feeling of relief that this effort would benefit so many untold others. Mavis FitzRandolph (1954) noted: “It is in her hands, and the hands of all who teach quilting, to see that it is passed on alive to the future”. I felt I had begun to repay in part the great comfort and pleasure that this practice of quilting at the frame had always offered me. More than the solace of a hobby, this practice has given me a framework to make sense of the world. To contribute to tangibly demonstrating the value of creative labour to historical thinking. I was itching to get back to my frame, but a busy Christmas needed a quick dopamine craft hit – and some warm floors for cold feet. A rug was the obvious next place for my explorations of the power of recreative making.

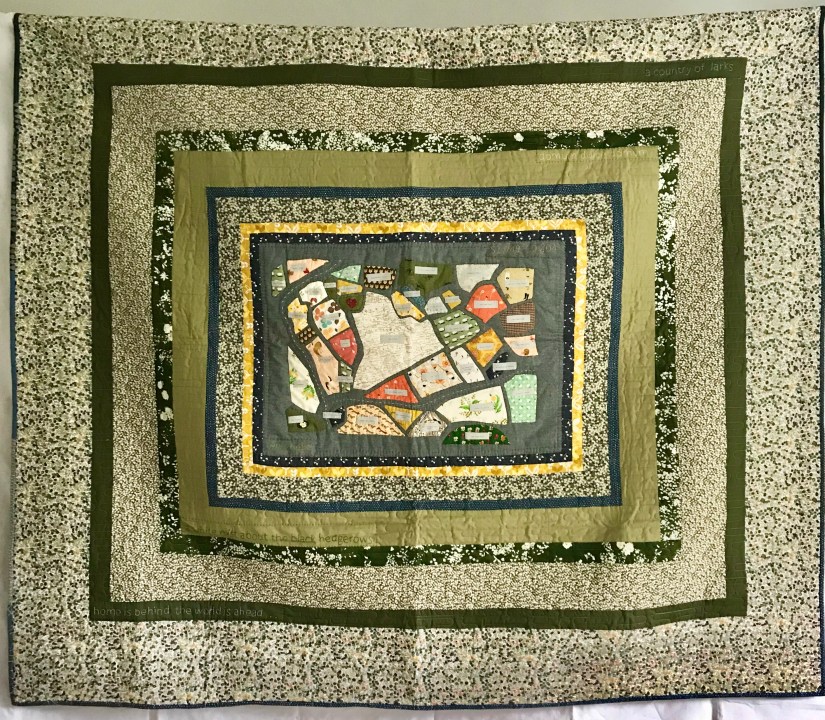

Quilts and rugs aren’t often considered together but they ought to be. They share a tool – the frame – but they also share a creative intention and reception expectation. The quilt and rug makers of the past largely made their domestic textiles within small circles of materially literate audiences made up of people they were related to, were neighbours of, or lived locally to them. Whilst those makers stitched within a small geography they laboured within a sense of a deep and intimately populated past and future.

In the past quilts and rugs were made using knowledge and tools from people their makers knew and loved, and they were made with an expectation that they would be viewed and used by related people. This often included generations anticipated but not yet born. This is a kind of ‘social’ form that we tend to pay little attention to today when we understand ourselves as islands of individuality and obsessively measure the flat, parallel, and largely unconnected ‘reach’ of modern influence on ‘social’ media or through audience measurement. But this much richer, more complex and emotionally charged audience equally impacted what people made – and crucially, what they thought about the work they expended to make objects. Our advocacy work for quilting in the frame engages with this ‘influence’ as it works to protect the craft in the future, on behalf of people from the past. Rug and mat making reflects many of the same impulses.

Making a rug that reflects the makers life is a kind of old-school content creation, in that it is a media which reveals truths about the makers inner life for the audience who will use and consume it.

Having any kind of public platform (particularly on the internet) these days can feel heavy. There is both an expectation and fear attached to this kind of exposure. It is possible that we have reached the beginning of the end of this mass-sharing experiment, we are all tired of this form of scrutiny, and I certainly feel that myself. Yet we all want to be more connected. Social media promised to connect us, but the shared endeavour and collective action that sustained people in the past seems further away than ever. These are large scale societal tectonic plates that our individual practice of craft sits within.

To talk about craft or making is also to talk about the organisation of society and the meaning of life. What maters to us and what is important. What we make and do defines who we are and how we show up in the world. Rug making is a form of political defiance when you title a photograph which centres a rug frame as ‘Miners Strike’. This 1892 image in the collection of the Beamish was reputedly found, annotated, in a rubbish dump. Images like this remind us that resistance was rooted in the camaraderie of shared labour. Making do was always political.

The frame is inherently political as it makes space for the expression of values. It quietly, insistently, reminds us of the power of collectivity. It gives us a hallowed space, bowed head to bowed head to learn about others, to ask questions and share worries. It restores a sense of how we are not dispensable islands of exploitable digital data, but instead are uniquely connected, impacted and affecting those who surround us. It tells us we are all makers and not just consumers as it slowly and meticulously, democratically and painstakingly demonstrates the value of using our hands to make tangible things, and how that also builds us – our sense of selfhood, our confidence and our self esteem as well as our sense of our own social value.

As I considered all of these complex considerations which shape my working life as the TV news spewed more incomprehensible skullduggery from across the globe, I decided we all needed a holiday, we tuned out and put up a rug frame and we embarked upon a short hiatus from engagement with the world, instead immersing in the gentle, egalitarian craft beloved of so many families before us.

The rag rug (and its frame) has been a companion in my research journey into the history and significance of the quilt frame. Accounts of quilting are often found in original sources which also describe rug making. Quilt frames could hold a large rug, rug frames are sometimes confused as small quilt frames. Many quilt frames have transited through our ‘rehoming’ program where we match old frames with new owners – sometimes the frames we are given have been rug frames. Rug making, like quilt making, suffers from the veil of domesticity – often outside of formal written record keeping of craft, outside of or invisible to paid commerce. Arguably rug making suffers more than quilting from the association of the objects with utility, yet its higher frequency ( rugs wore out more quickly than quilts yet more were made) of making renders it visible in more accounts of making-life in the past. Like quilts, its transplantation to the American east coat and subsequent veneration as a pioneer craft has also seen it more highly regarded in the US than in the UK.

To learn more, the informative podcast by Haptic & Hue featuring rug historian Emma Tennant, tells more of this transatlantic and disporiac story. Rosemary Allan’s excellent book “From Rags to Riches’ for the Beamish Collection explains the north country history of these textiles. The late textile artist Heather Richie long engaged with the local landscapes of Swaledale in her beautiful rugs. You can read more about the craft and its practitioners here.

Last February I travelled north to see the exhibition of Winnifred Nicholson’s rag rugs at MIMA in Middlesborough. I expected to love it, because for many years and aware of her creative expression in this medium, I have been bewildered by its absence in many other explorations of her artistic work. This exhibition solidified many of the feelings that I had been having about the often still ignored complicated intersection of mothering, domestic life, creativity and societal measurement of worth.

In celebrating the art that Nicholson made with her children and neighbours, in response to her domestic life in a loved landscape which connected her to her matrilineal history this exhibition, I would argue, takes you much closer to the impulses that also informed her paintings. Her beautiful paintings are tender and personal. But the wider community of art making which she facilitated in rug form revealed the neighbourly and friendship ties collaboratively central to her life.

I loved the richly emotional story that this exhibition told of Nicholsons personal and social life which showed a woman enmeshed at the heart of a rich network of social and generational connection. That she chose to encourage the depiction of this world in rug form amongst those around her seems obvious. An impulse so resonant of my own experience of quilt making.

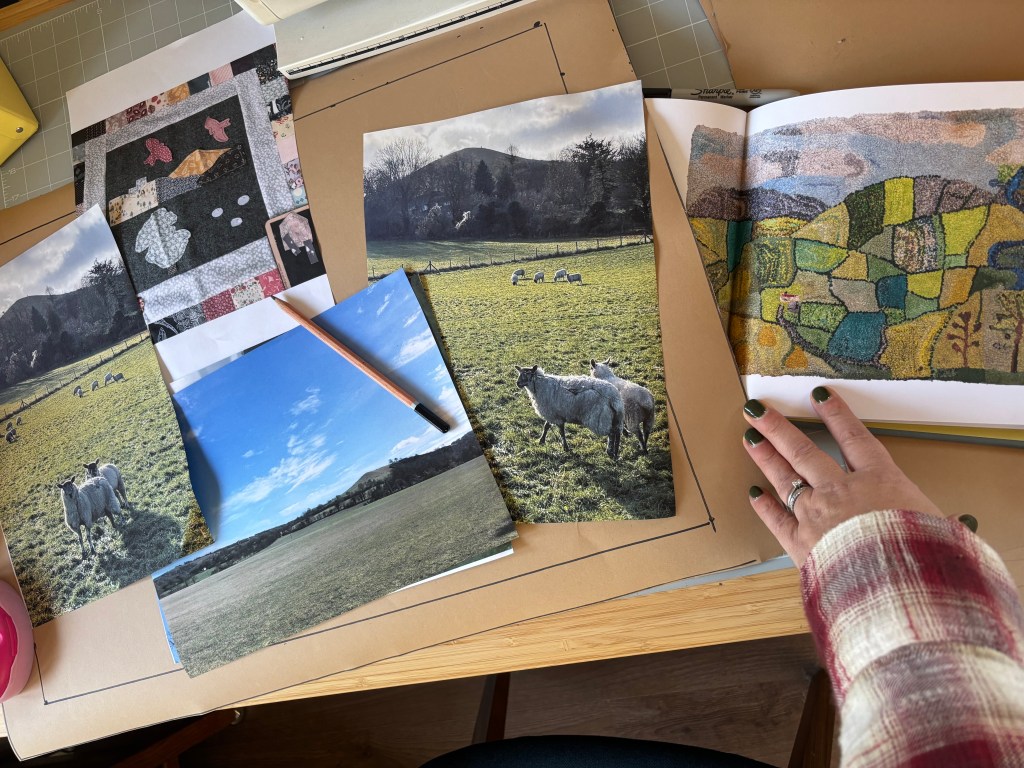

I absolutely loved the landscape rugs designed by her grandchildren. Far from parochial they represent one of the great debates that society is playing out at the moment because they remind us of the power in the ties to landscape and place that many of us feel so centrally. In a capitalist globalised world where labour flexibility has been so highly prized, the post -pandemic pendulum swing back to localness (whilst dangerously manipulated by many malevolent voices who seek to use love of place in ways that exclude rather than include) does reflect many people’s lived experience of the powerful draw of landscape and its role in a sense of craved belonging. As someone who never felt like they were a citizen of nowhere, but instead always felt that loving your own patch gave greater empathy for those who had to leave their beloved patch, sense of place has always been important in my making.

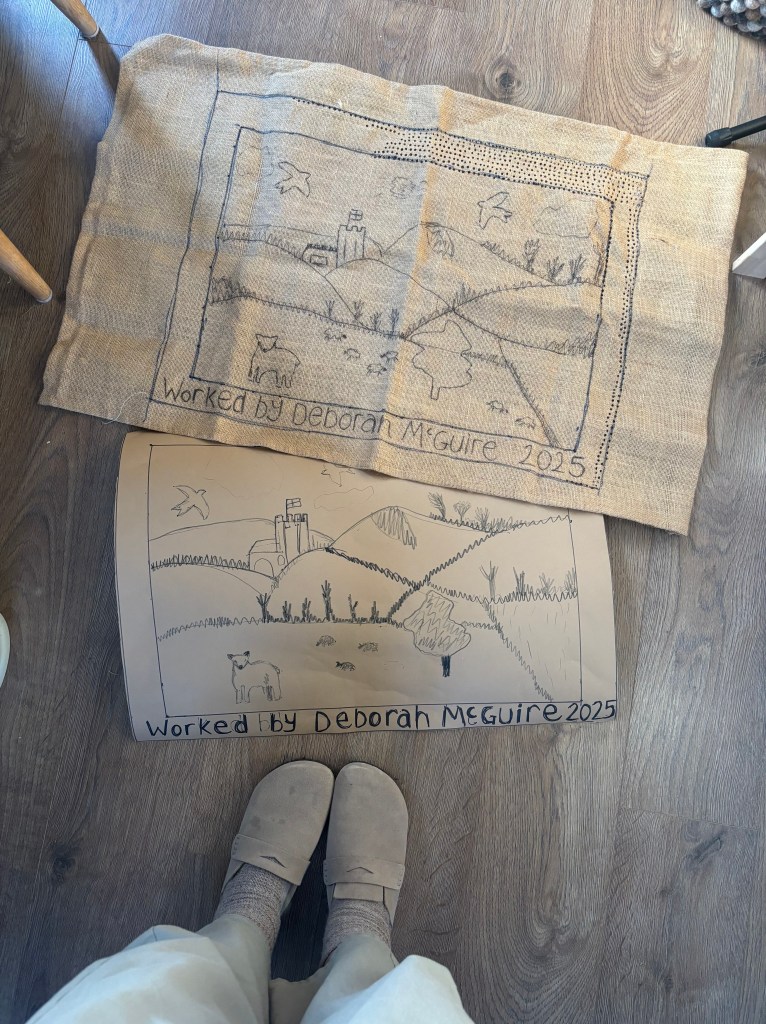

We love our local patch on the downslope of the Chiltern Hills. For many years i’ve made quilts to memorialise my love of the views that my dog walks revisit week after week. As a family, all of our favourite memories are backlit by the silhouette of these ancient uplands. Good news and sad news, highways and holidays, wet days and baked in sunshine all processed by a walk up to the top of the windy hill. The view, so familiar to us, is never static and boring. Of course this landscape would inform our shared design.

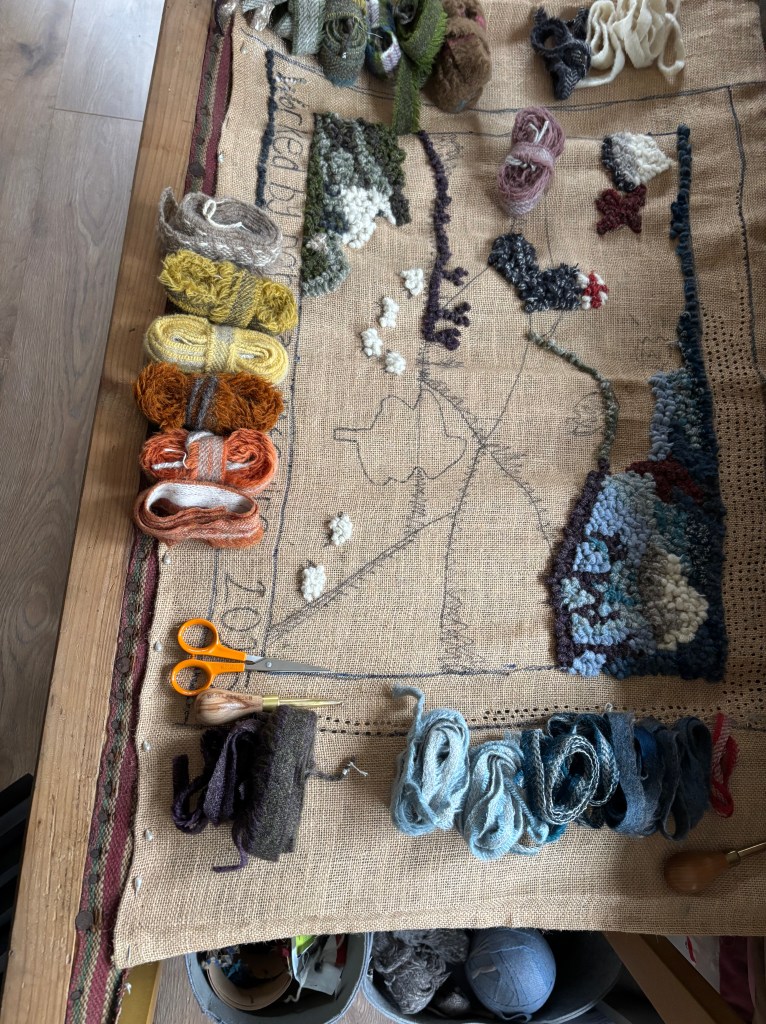

A real draw of this rug work was the haptic deliciousness of the materials that we got to handle.

I’ve been collecting woven selvedges from the textile makers that I meet as I travel around the countryside in my academic life, many of these from the wonderful work of north country weavers whose work I admire and who I have had the pleasure to meet and talk textiles with, and so this is a little way to weave some of their textile magic into something of my own making.

My tool, the frame, was donated from another talented textile maker who saw it in a local farm sale and couldn’t let it go to firewood. The frame, farm and woven wool all came from the same tiny geographical patch – another landscape very dear to me. This project felt like a love letter to both a place and a locally rooted practice that has long had my heart.

Asa Christmas swirled around us we stole quiet moments to add a few lines of texture to the rug.

The technique we chose to use was rug hooking, where a strip of fabric is held beneath the hessian and pulled or scooped up by the hook to form a small loop. Rows of loops continue unbroken until the length of fabric ends. This perfectly flexible and pragmatic technique allows for the use of all shapes and sizes of scraps and can be done by anyone.

It is work that accommodates many hands. There are different jobs for those who prefer to cut neat strips of fabric to those whose creative flourish is waiting to be unleashed. The perfect communal and sustainable practice in a busy multigenerational household.

The frame is small, it stands happily behind the door when space is tight, or squeezes into a small space when too many people take up too much space at Christmas!

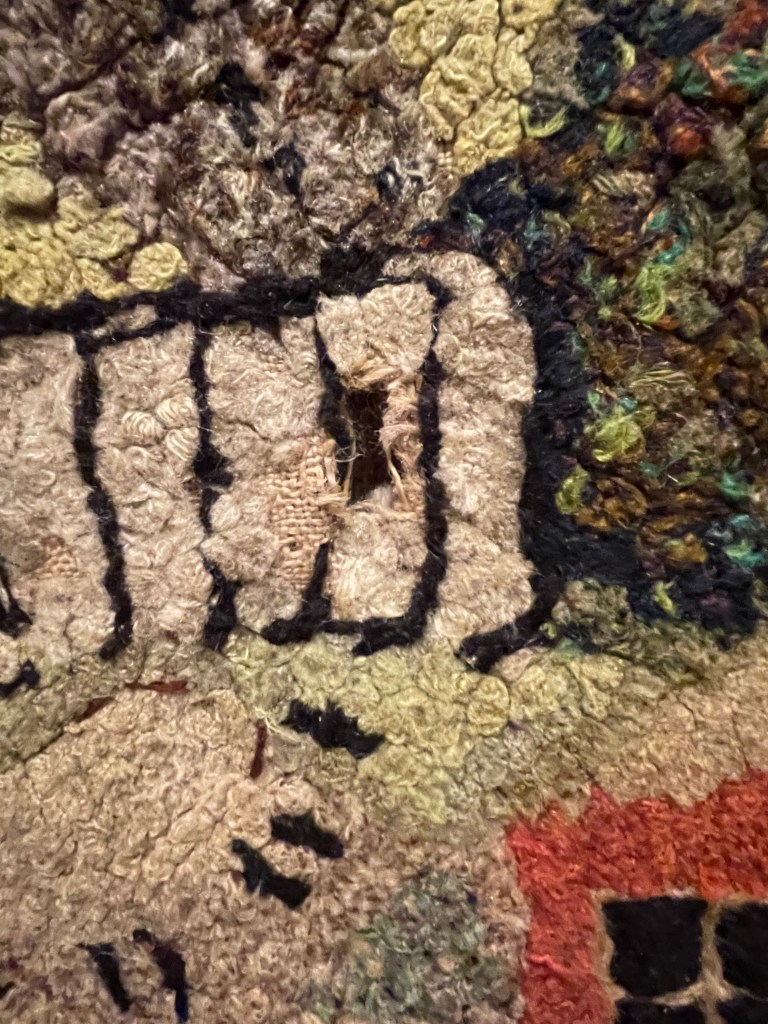

But, slowly and surely it was completed. Many hands make light work. Over the course of three weeks family and friends contributed, different makers added their own style, picked colours and suggested improvements. We laughed and talked, someone cried, life is full and complicated and being squeezed between generations as many of my age are can feel heavy. The deep generosity of the tactile warm rug absorbs all of these aspects of a full life. Perhaps they always did. Perhaps that’s why. When we forget or dismiss craft we are usually denying a part of the breadth of the emotional experience of life and how we choose to express it, to be forgotten or ignored too. This Christmas this little rug bought us joy. In a world full of heavy news, the softness of making our own corner warmer, kinder and more connected was powerful.

Since the start of January the rug has been in heavy use, even whilst I’ve been too busy to write about it despite these thoughts always bubbling under the demands of the ever-present to-do list.

Well, of course we are hooked. A new years and another rug is in the frame, new colour scheme is in play….