Emotional Journeys: The British Quilt in Space and Time.

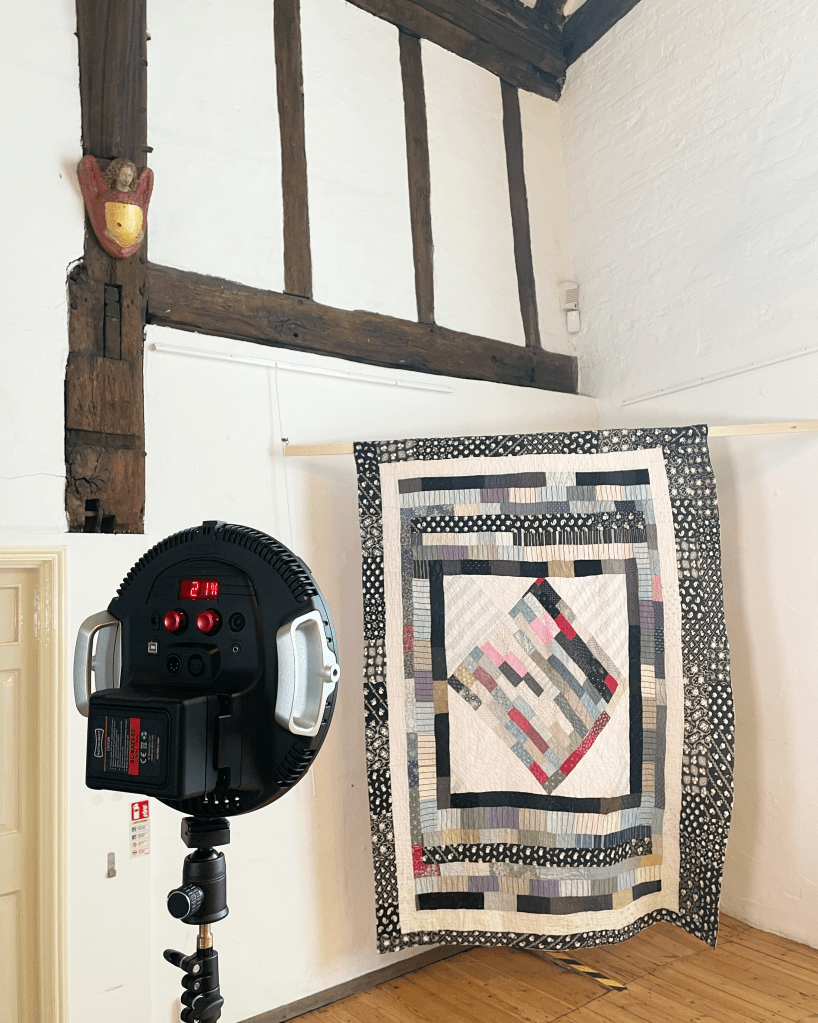

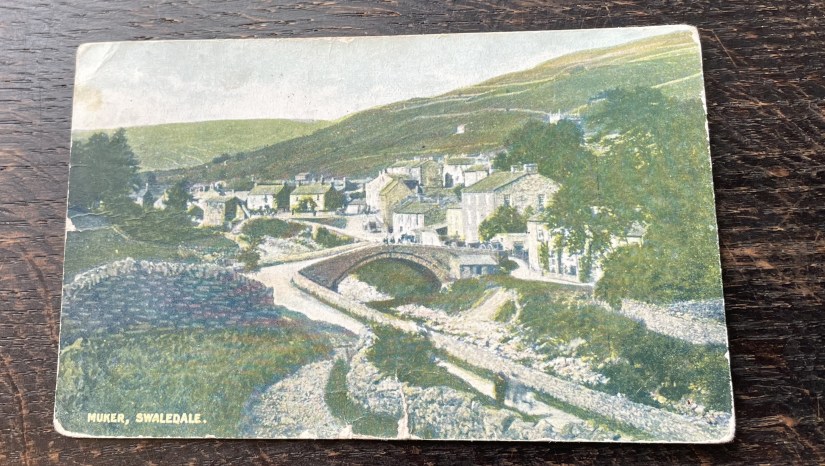

Last summer I collaborated on a lovely film which explores why quilts survive within families. I chose to talk about The Swaledale Farm Quilt, probably made in the 1890s by Mary Jane Dent Kilburn in the Yorkshire Dales village of Muker, high in the Swale Valley. This quilt is now in The Quilt Collection of The Quilters’ Guild of the British Isles.

This film was made by Lily Ford for The Inheriting the Family Network, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, with the support of the State Library of South Australia and The Leeds Family History Centre, in collaboration with musicians Patricia Hammond and Matt Redmond and the Keld Singers courtesy of The Dales Countryside Museum and images by Marie Hartley courtesy of the Special Collections of the library of Leeds University and the Hartley family.

The Inheriting the Family Network explores the role of emotion in explaining why some objects and stories (and not others) are transmitted across generations and from the private sphere of the family to public spaces like museums and archives. The network brings together academics from across the world, along with heritage, museum and family history professionals, and members of the public with an interest in family history and inheritance.

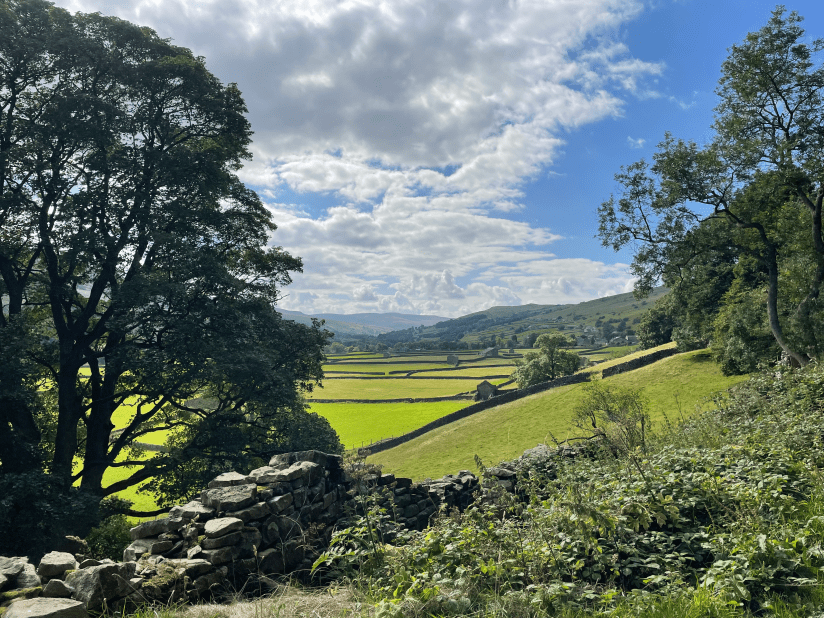

To make the film I had the pleasure of travelling to beautiful Swaledale, spending time researching this quilt and its home. We enjoyed exploring archives of photographs and folk music to bring to life the world in which this quilt was made and used. For the film, musicians recreated a Victorian song about quilt making and we used recordings of folk songs captured in the 1950s and used old photographs of this area. The film was also made for a non-quilting audience, and so I was asked to demonstrate the vernacular skill of hand quilting in a frame to help viewers to picture how a quilt was made and why it might become an object associated with emotions and memories for the maker and their family.

The film was such fun to make, I hope that you enjoy watching it! You can see other films made for this series which explore more aspects of family inheritance at the Inheriting the Family Network website here. These films are free and shareable so do consider using them to initiate discussion in your quilt group or amongst sewing friends about the role that quilts might have, or once had, in your family. I always love to hear quilt history stories, old and new.

I chose The Swaledale Farm Quilt because I wanted to tell the story of an ‘ordinary’ quilt from an everyday background. When we think about the quilts that have survived through history we tend to think about elite quilts, made of valuable materials or created with complex needlework. These quilts tend to survive because their value has been recognised for longer, and they tend to come from families where holding on to objects was usual. Yet most of us come from homes where things were used up, lost or sold over the years, where objects needed to be useful as well as beautiful, where migration or displacement meant that objects got separated from people. In families, objects can become important because they allow history to be told, and many kinds of families had quilts, so it is important to capture their stories too. As a historian, quilts can be important objects to help us learn about the emotional lives of people in the past. In the things that individuals and families emotionally valued is much bigger history about what societies valued. When we learn how people saw themselves and their families, what they valued and what they passed on, we can also better understand the world in which they lived. This quilt, like countless tens of thousands of others, had an ostensibly quietly ordinary life. But when we look beneath the covers of a quilt we see that no life is really ordinary, and this ordinary-and-extraordinary quilt can tell us much about its owners and makers as they made, and lived through, history.

This quilt was made after 1890, probably by a young girl called Mary Jane Dent before she married. She likely had a connection in the drapery or dressmaking trade because she used a sample pack of fabrics which used repeated designs on different colours, or, in the unusual black print, one colour with lots of different patterns. Her quilt was simple in construction, yet is still – even today – striking in its bold modernist design. Mary Jane quilted it in an overlapping plait design common in that region as a practical and pragmatic pattern that was easy to mark and easy to quilt in a frame. Mary Jane was born in a farming family, they probably had made quilts with their mother and she went on to marry a chap from the village where her mother had grown up, perhaps the son of a friend or neighbour. Her quilt was put to work in the Muker farmhouse where the couple lived and it remained there until it passed to the museum in the 1990s.

Perhaps Mary cherished this quilt at the beginning, it remains in good used condition for its age. Did it wrap a new child or cheer a bedroom in the early days of her marriage? Perhaps its familiarity and association with home eased the upheaval of the move for a new bride. As her family grew and her son took on the farm when her husband died, perhaps the quilt became an object fondly associated with her son’s childhood memory? By the midcentury the farm also supported her grandchildren and in time the farm passed to a new generation. Mary Jane lived a long life, and remained at the house until she died. The farm passed between brothers and then to sons, by the time the quilt passed to the museum the story of its maker was hazy and memories of the quilt were connected inextricably to the house – remembered on a bed, stored in a cupboard, perhaps finally destined for a tractor cover. As generations pass by, an object’s value changes. This quilt was practical and robust, useful for keeping a warm bed but also for covering a tractor? The final donor was a cousin, living far from the family farmhouse, which by now was being converted to a bed and breakfast or holiday let. The quilt finally became a symbol of a changing rural society as well as one family’s past. Yet the social history value of this old quilt ( and others from the same family) was recognised, and the quilts passed to the museum. Their value to history is that they hold all these multifaceted stories within their stitched layers.

This quilt is typical of the long lives of old quilts. Sometimes emotional, sometimes taken for granted. ‘Owned’ by different generations who value it for different reasons. Sometimes carefully kept, other times left in a cupboard or covering old furniture. Some quilts are passed on with obligations, others just live their lives gently alongside a generational family until something jolts a reassessment. This film is designed to show the labour of quilt making that long ago women and men undertook, and it asks audiences to reconsider the quilt as a text rather than just an object. For those of us who make quilts today it encourages us to think about the wide range of ways that quilts might be used and kept if they outlive us. You see, loved quilts are both the ones that survive and the ones that are used up. All quilts have the ability to capture and tell history. Whether our quilts are cherished or just practical, forgotten or cherished, on a bed or in the dogs bed, all have value if we want to tell a holistic history of all the range of human emotion.

My academic work ‘Emotional Journeys: The British Quilt in Space and Time, 1750-1920’ explores quilts as objects which hold histories within them. I look at moments that quilts pass across spaces and through time, because in those moments of displacement or change reveals emotions connected with, or displayed in quilts. Whether that is moments of family inheritance or migration, moments where quilts reveal things about bodies or souls, whether they connect us to communities or to the past – it can all be read in the folds of the ‘ordinary’ quilt. You can read more about my academic work here. You can read my MA Dissertation, which explores how quilts reveal the emotional connections in families; ‘Remember Me’: Domestic Textiles in Britain, 1790-1890: Memory, Identity and Emotion here.

Thank you Deborah, that was lovely. I live in Northumberland, and treasure a wholecloth quilt in pinks and yellow, which a friend bought for me in a charity shop for £25! It is all hand stitched, apart from the edge stitching , which is turned in and machined. I love it as much as my own quilts. What a wonderful fulfilling hobby this is! I really enjoy your posts, thank you for taking the time to put them together. Loraine x

LikeLike