This quilt is the product of the melding of three women’s creative choices; Deborah, Elizabeth and Frances, and this post is the story of our 170 year collaboration.

The road through Baldersdale in the North Pennine Dales winds past gentle lush fields along the valley bottom climbing relentlessly up to the flat high moor top reservoirs at the head of the valley, higher and higher until it reaches Low Birk Hatt Farm. In 1972, a Yorkshire TV researcher was walking the Pennine Way, he stopped at the farm and met Hannah Hauxwell, who farmed this remote land alone for 27 years after the death of her parents and uncle – and he subsequently made a documentary about her life. Hannah became perhaps the first reluctant national reality TV star, but when she moved from the farmhouse, inhabited for three generations, and finally died in old age in 2018, her estate included thirteen hand quilted and pieced quilts, which were auctioned in 2019.

Hannah talks in her 1989 memoir Seasons of My Life, of her paternal grandmother Elizabeth’s ability at a frame, describing both her and Hannah’s own mother as, ‘clever with their hands, making mats and quilts. Grandma laboured for years with her frames’. This quilt was made around 1880, from fabrics perhaps printed twenty years before.

Hannah’s grandmother, Elizabeth Bayles Hauxwell (1862-1940), marked this quilt in about 1880 with her maiden initials EB, embroidered in colour safe red thread as was a common laundering practice. Her granddaughter, Hannah, describes her as a talented needlewoman; dressmaking for neighbours, remaking an old quilted petticoat into a children’s doll for Hannah, and giving sewing lessons for the local Methodist Church.

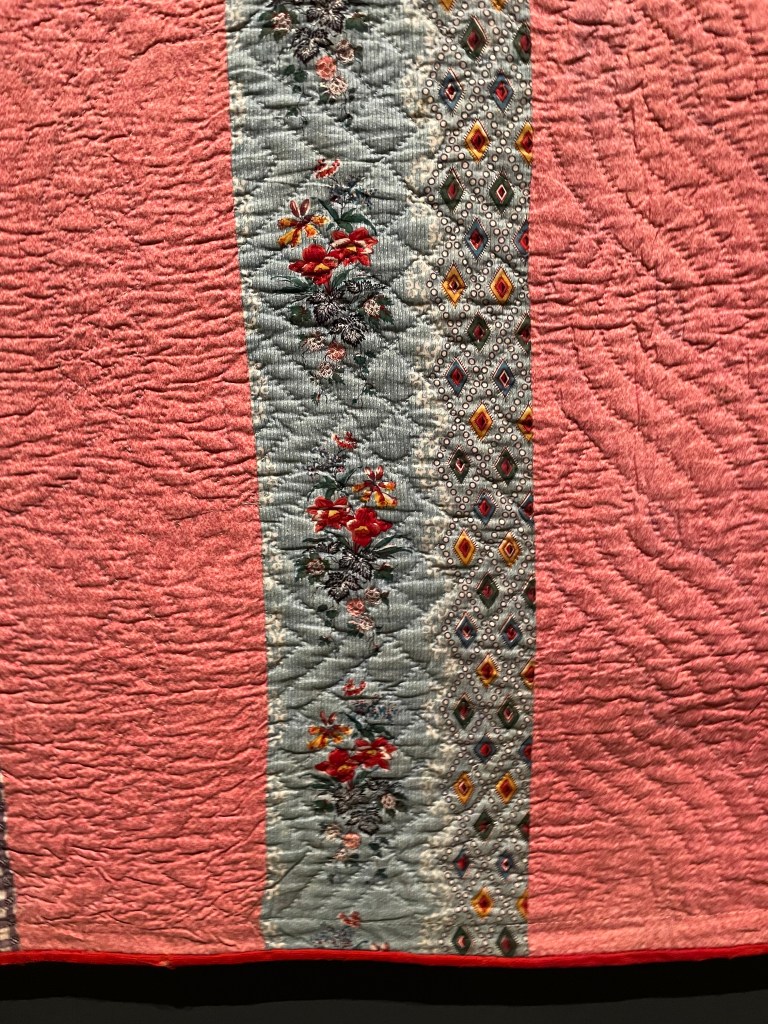

This pretty strippy quilt was bought by The Bowes Museum in 2019, and I loved seeing it on display when I visited last summer in the 2021 exhibition. Visiting in the last warm days at the end of summer whilst staying in the Dales, our week of post-lockdown-holiday was marked by blue skies and perpetual heathery purple ground, when I looked at Elizabeth’s quilt I felt like you could lie it down on the ground and it might blend perfectly into the palette of the place. As you’ll realise if you scroll through more of these blog posts about my making, I love nothing more than a quilt rooted firmly in place; I knew that I would make my own version of this north Pennine classic to evoke precious holiday memories until I could visit again.

Elizabeth’s quilt is unusual because it eschews the usual choice of the two colour strippy more common later, like in this other north country strippy I own ( picture above), and instead it links two distinct quilting periods in a marriage between the fabrics found in ( often frame style) quilts made until 1840 in these pretty floral cottons and this later modern strippy construction. Elizabeth used long printed cotton strips, even utilising the printers fent ( the test section of the print run, usually discarded) to make up her quilt top. The widespread adoption of the labour saving sewing machine after the 1870s made the long seams of strippy quilts a perfect choice for women who wanted their quilting to be the main event, probably why they became so ubiquitous then. Was the strippy side the front or the back? Study of extant quilting suggests that perhaps the strip was also a pragmatic evolution that made the marking of wholecloth quilts simpler, these quilts were likely designed to be seen from either side ( although modern audiences tend to consider the pieced side the ‘front’, a distinction that was likely reversed, if made at all, when these quilts were originally sewn).

Quilting in a frame, as Elizabeth did, offers the seamstress great freedom because the tension is perfectly held by the fixing oak pegs which flex against the gentle structure of the wooden shafts, leaving the two hands free to concentrate only on the rocking motion of the stitch, but it also imposes other restrictions in its immobility. Hand quilters know that by far the smoothest and most enjoyable quilting pattern is one that winds towards the stitcher, unfolding complex shapes ever onwards towards the maker. Strippy quilts harness this pleasure and their combination of timesaving ease in construction and instinctive quilting made them a firm fast favourite form amongst the frame quilting women of the North Pennine and Durham Dales in the last decades of the nineteenth and first decades of the twentieth century. I knew that my piecing would seek to reference Elizabeth’s, in a palette of heather and summer skies, but I wanted to draw on the creative imagination of a third contributor to influence the hand quilted patterns for this new piece of quilting.

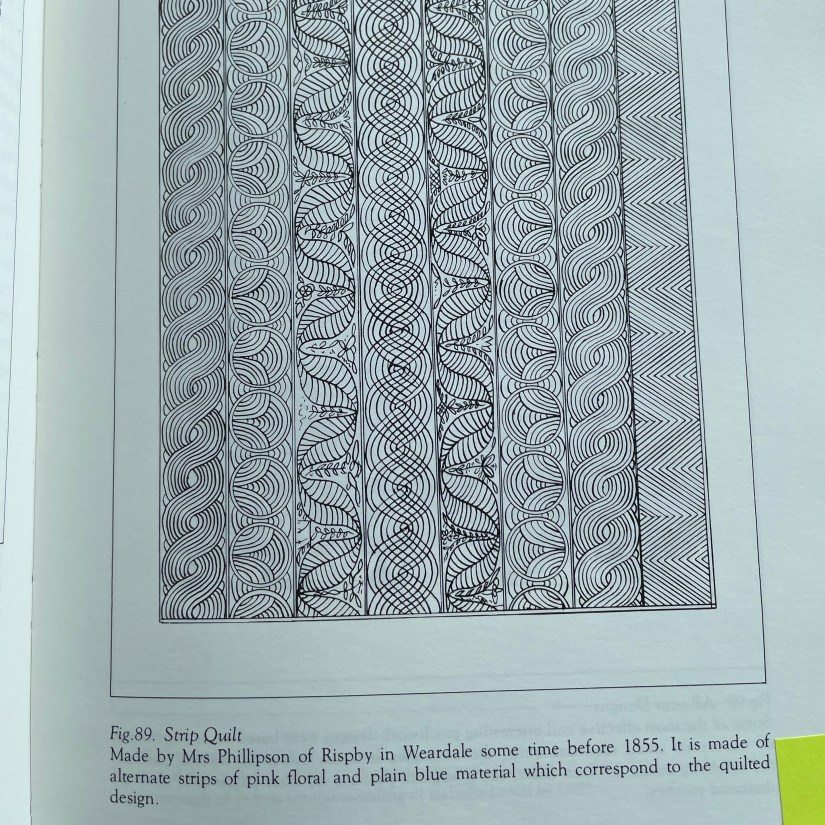

Elizabeth Bayles in Baldersdale inspired my piecing, but for the inspiration for my quilting pattern I looked over the moortops to Weardale, following the winding country road north through the heather for 20 miles. As the birds fly, the next valley is a near neighbour, yet it is a circular journey which would take at least 30 minutes by car today, following the convoluted contours of the becks and gills that skirt the high Black Force Waterfall in this beautiful part of England – to Rispby, nr Rookhope in Weardale to visit the quilt maker, opaquely named Mrs Phillipson, whose strippy quilt pattern had haunted me for 20 years.

Mrs Phillipson made a strippy quilt ‘at a point before 1855’ according to the attribution in the Beamish Museum. This quilt’s elaborate and idiosyncratic pattern was drawn as a line picture for a 1989 book called The Folk Art of the North Country by Peter Brears, a book I had long studied. This quilt caught my eye because it was so early, strippy quilts from before 1870 are uncommon ( in museum collections at least) and the patterns of this quilt look different to those seen later on more common strippy quilts, they had more in common with the patterns seen in the century before on silken petticoats and quilts. I knew that this was the quilting pattern that I would look to draft and bring back into modern use.

The maker of this illustrated quilt pattern is only ever referred to as Mrs Phillipson of Rispby, a nomlacure common to accessioned quilts in the middle decades of the twentieth century which is a bug bear of mine as a historian who haunts genealogy websites, not least because it complicates any search and more importantly robs married women of even the dignity of a first name of their own. I set out to bring Mrs Phillipson back to life through her beautiful quilting. My accademic and making lives often overlap, and so I bought some of my research time to this little side project in my hunt for Mrs Phillipson in the records.

Rispby is a place that no longer exists as a google maps search location. The road through Weardale winds through a series of narrow villages and hamlets, shaped by the steep geography between road and river into strips – shapes much like the long strippy quilts that were so commonly made there. A steep sided valley, the houses hug the road and they perfectly map the once vibrant lead mining industries that filled these valleys with families, methodist chapels and pubs. Still picturesque, some villages survived the decimation of this industry by the time of the First World War by falling back on the farming that had always been the wingman to the uncertain wages in the pits, and finally on tourism, which boomed from the turn of the twentieth century and is marked in the many charming black and white postcards which remain, with their cheery messages of British holidays in the beautiful dales. Risby no longer merits its own place name, Rookhope is the closest approximation to the address at Knock Burn where the Phillipson family lived.

Mrs Phillipson, let’s call her by her given name, Frances, was born in the late 1820s ( the record is hazy) and her parents were George and Ann Graham. in 1841 she is listed as 15 years old, and in 1851, still at home, is recorded as aged 29 (vague arithmetic?) living with her mother and six siblings stretching in age from 29 down to little Arthur who was 7. It’s likely that this was when she made her quilt, as a twenty- something unmarried woman in a busy domestic household where maternal quilting skills were routinely passed on to daughters just as the Bayles/Hauxwell family had done; Frances and her two sisters would have likely sewn with their mother, Ann. Ann Graham was born in the eighteenth century, it is thus not too much of a stretch to see why the quilting patterns that Frances used have a resonance with the patterns of the century before. They are listed as living in a ‘township’ in the parish of Allendale, a township was a semi permanent mining settlement high in the Allenhead and Wearhead valley junction, an area that would have been full of mines and miners including their father. At some point in her mid to late thirties Frances eventually married Thomas Phillipson, a farmer nine years her junior who worked first as a lead miner, but by 1881, at the age of 49 he was listed as farming 36 acres. They had one son, Joseph, probably a reflection of Frances’ late age at marriage and in 1901 the couple still lived at Knockburn, now farmed by their unmarried 45 year old son Joseph. Frances lived a long life, dying in 1908 at the age of 85 ( or thereabouts, counting birthdays remained a vagary!).

In melding the creative choices of Elizabeth Bayles and Frances Phillipson with my own I look to create a new quilt with its roots in a meaningful history. The patterns and fabrics that these women chose were not arbitrary, and thus they tell us much about their lives and influences. Just as they made quilts of their time, I too looked to the fabrics of my time, using a range of fabrics including a sateen flat sheet, this pretty floral printed Rifle Paper Co print which I had been hoarding for just this project for a few years, and some splashes of heathery purples to better evoke the places that these quilts were made. I pieced the quilt as soon as I came home from my holiday in summer 2021 with the images of the beautiful moors on my mind.

It finally made it on to the frame in a snowy weekend in February 2022 and that was when I christened it the Too Long a Winter Quilt, named in reverence after the title of one of the documentary films which followed Hannah Hauxwell battling through a long cold winter on her remote farm. This countryside is beautiful but brutal, it pays to remember that to avoid idealising this life. I hand quilted it in my antique flat frame as winter melted into spring, finishing at midsummer in June 2022

This summer I took this quilt back to the moors on the most glorious day. In the valleys the combines toiled, but on the moortop it was just windy birdsong and plaintive cries of sheep. The clouds parted and a beam of light illuminated the quilt.

This was a world of extremes in the nineteenth century when Frances Phillipson and Elizabeth Bayles stitched their beautiful quilts. Mining offered periods of boom or bust, harsh winter and golden summer transformed their landscape, poverty and hard work juxtaposed with beauty and aesthetic yearning, warm quilts for indoors evoked the wild beauty outside, these quilts were both art and function, individual but of the community. To appreciate the creative work of these women we need to consider all of these dichotomies. Their work is art, their work was labour, we keep their legacy safe in stitch when we remember them in our own new work, clear eyed about their lives, in these beautiful unyielding places where they stitched.

I’m looking forward to sharing more of my PhD research into the makers of this region, celebrating their creativity and ingenuity in due course.

That’s lovely – both the quilt and the stories. I never really thought of a modern quilt being able to have such a sense of ‘place’ in its colour and design but I’ll certainly try to include that when I think about my next quilt.

LikeLike

What a wonderful read about the strippy quilts and your journey of research and culmination of your own, beautifully hand quilted strippy quilt.

I thoroughly enjoyed the history of the women who made them and the links of the industries and environment that shaped the colours and stitching patterns.

I certainly look forward to more of your writings and quilts!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a beautiful and meaningful quilt and I very much enjoy reading your research about the makers that inspired you – and seeing their wonderful creations too. I’m currently making a quilt for myself (unusual as I normally make them for other people) and you’ve inspired me to have a go at including some motifs that hold personal meaning. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was told by my mother-in-law who taught me how to quilt that quilters leave so much of themselves in their quilts and gain so much in the process that both the life of the quilt and the quilter live on in the telling and retelling of its life. I don’t think I truly understood what this meant until I read this post. Your quilt will allow those quilts and quilters who came before to continue a never ending story of life well lived, cherished and enduring. Thank you. It’s a beautiful quilt filled with warmth, history and skill.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Elizabeth’s quilt was the one I stood at the longest in my visit to Bowes museum last year, mesmerised by the stitching and loving the quirky addition of the fent in the piecing. I often wonder about the hopes and dreams stitched into old quilts. Modern quilts, whilst having their own stories, differ so very much being made by choice and not often by sheer necessity, although still with love.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really enjoyed reading all your information about Elizabeth and Frances and their families and well done for finding out who ‘Mrs Phillipson’ was! I too love researching quiltmakers and like you, find it a real bug bear that often they are only known by their married name. What a super story to have for your quilt – will you be bringing it to the BQSG seminar? Regarding Frances’s birthdates – apparently in the 1841 census, the age of those over 15 yrs was supposed to be rounded down to the nearest multiple of 5 – so Frances could have been as old as 19 in 1841.

LikeLike

Did they use raw wool as batting? I know so little of the Era and area. (Montana USA quilter)

LikeLike

Very inspiring post. Thank you for sharing, and congratulations on making such a lovely and meaningful quilt.

LikeLike